|

Laura Zanotti, Emily Colón, and Dorothy Hogg

On December 5, 2019, at the UNFCCC COP25 meetings in Madrid, Spain, United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Victoria (Vicky) Tauli Corpuz urged negotiators and decision-makers to add provisions for human and indigenous rights in Article 6 of the Paris Agreement and reminded parties to fulfill their obligations of signatories of already ratified agreements and declarations on human rights. At that same time, Vicky noted sole dependence upon action at the international scale was not viable and announced the formation of a new indigenous climate action network where grassroots and on-the-ground efforts can be sustained and linked. Vicky was a speaker at a Blue Zone event in the Spain Pavilion with two other Human Rights Defenders. This is just one of many events we have seen in the credentialed Blue Zone, located at the IFEMA complex, which draws attention to the need to address human rights, indigenous rights, and other rights when formulating climate action solutions. Challenges in Madrid The number of events led or organized by Indigenous Peoples’ organizations in Madrid has been wrought in the face of steep barriers. On October 30, 2019, the organizers of COP25 Santiago, Chile, announced, in the midst of protests, that they would be canceling the COP there that year, which was just shy of a month away. Days later, the UNFCCC confirmed the meetings would still take place but would be relocated to Madrid. While several applauded the quick adjustments, for Indigenous Peoples and other marginalized peoples attending the event, this posed new logistical, geographical, financial, and other barriers to engage in a meeting that already is not easy to access. In a Cultural Survival article, Andrea Carmen states, “I am disappointed that the COP Secretariat could not wait until Chile resolved the crisis to reschedule, or at least moved it to another location in South or Central America. Many Indigenous Peoples from Chile, the Andes, and the Amazon basin were coordinating to attend. There were also events planned for the Indigenous pavilion in Santiago outside the UN venue for those without credentials to hold meetings, discussions, share developments, and arrange presentations on climate change impacting Indigenous Peoples and solutions based on our own knowledge systems. Large numbers of Indigenous Peoples that planned to be in Chile will not be able to be in Madrid, especially the Peoples from the region,” (Andrea Carmen (Yaqui), executive director of International Indian Treaty Council and member of the UNFCCC Facilitative Working Group for the Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples Platform (LCIPP). Others in the article support this statement, noting concerns about the move and the ability of indigenous leaders and organizations to mobilize in the same way by relocating to Madrid. Nonetheless, the P2I team sees a strong and growing coalition of different peoples and constituencies, including Indigenous Peoples Organizations, Youth non-governmental organizations, and the Women and gender constituency, who are advocating for rights to be part of the climate change negotiations, and who are also advocating for safeguards in place, public participation, and access to information for climate adaptation and mitigation. This is in the face of a COP which several at the congress feel has been co-opted by corporate sponsorship, privatization, and neoliberal logics. COP25 Chile/Madrid is taking place in many different spheres. The IFEMA Zone at the Feria de Madrid stop is where the official Blue Zone and Green Zone are housed in the city. While you need to be credentialed to enter the Blue Zone, the Green Zone requires online registration for admittance to the public. In addition, from December 6-13 a parallel event, the Cumbre Social por el Clima is occurring at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid. On its opening day, Minga Indígena, featured an all-day event with indigenous leaders around the world. Finally, the Cumbre de los Pueblos 2019 is still taking place in Santiago, Chile. Article 6 Article 6 of the Paris Agreement “aims at promoting integrated, holistic and balanced approaches that will assist governments in implementing their NDCs through voluntary international cooperation”[1]. The international cooperation mechanism that is being debated, negotiated, and developed at this COP, thus, has implications for non-market and market-based approaches to emissions. The urging of Vicky to include human rights and other rights in Article 6 would firmly locate rights in the operational part of the Paris Agreement, whereas now rights are only mentioned in the preamble. Wrapping up the week from the Climate March to Nix Article 6 From a climate march on Friday December 6, 2019 that brought together more than half a million people for climate action to several side events that featured indigenous rights, some are calling for removing Article 6 altogether as its emphasis on carbon markets and financing is an antithesis to climate action. As we move forward to the second week, we repeat some of the ways some Indigenous Peoples at the congress are calling for support: Some ways you can be ambitious, and support Indigenous Peoples this COP25 are:

[1] https://iccwbo.org/media-wall/news-speeches/article-6-important/ Guest Post by Maria Gabriela Fink Salgado and Eduardo Rafael Galvão Visiting Scholars, Department of Anthropology, Purdue University During a traditional ceremony Motere Kayapó and other Indigenous People record the event in the Moikarakô village, Kayapó Indigenous Territory, Pará, Brazil. Photo: Beprot Kayapó. In 2002, Dr. José Ribamar Bessa Freire, a Brazilian sociologist, identified critical insights on the perception and treatment of Indigenous Peoples in Brazil. Speaking specifically to the non-indigenous majority in Brazil, he identified many of the mistakes and misconceptions of Indigenous Peoples that persist today. These insights are revelatory. They show the ongoing prejudices against Indigenous Peoples, and how these perceptions and attitudes continue to obscure the rights and freedom of Indigenous Peoples.

We reproduce his list here:

We think this is a critical moment to revive these insights. From our experience, these misconceptions have not gone away, and in fact, we are seeing a resurgence of these discourses and narratives in popular culture. If we are going to move ahead with supporting indigenous rights in Brazil, as guaranteed by the constitution, and Indigenous Rights as outlined by the United Nations Declaration for Indigenous Rights, we need to continually recognize the negative impact these narratives have on Indigenous well-being and self-determination. We still do not know who we are as a Brazilian society. A reflection of such relevance in the current situation in Brazil, taken by innumerable aggressions mainly to the rights of indigenous peoples, and which unfortunately should not be exclusive to the South American continent. For this reason, we provide a discussion here on how these misconceptions are insidious, pervasive, and persistent. The first mistake The first mistake is the idea that all Indigenous Peoples are homogenous. In Brazil more than 305 Indigenous Peoples thrive and speak more than 274 different languages. And each Indigenous Peoples are unique in their language, lifeways, and worldviews, which are reflected in religious, culinary, artistic, literary and aesthetic diversity. Cultural diversity does not fit into a single representative generic category. To say "He is Indigenous" is an aggregating discourse that dismisses this heterogeneity. Furthermore, it fails to recognize Indigenous Peoples by their self-designation or their diverse ways of being. The second mistake The second mistake is to consider Indigenous Peoples and their cultural expressions as backward and primitive. This fails to recognize Indigenous knowledge systems and furthermore wrongly places Indigenous Peoples on an nonexistent cultural evolutionary scale. Indigenous Peoples are resilient and innovative, and have been subjugated to and still are influenced by over five hundred years of colonialization. As recognized by the Declaration of Belém, The Convention of Biological Diversity, for example, Indigenous knowledge systems are longitudinal and rich, and knowledge holders steward plants, soil ecologies, domestication of species, fauna and flora and even invisible beings (who protect human-environmental relations). Indigenous health systems and healers, such as shamans, provide diverse insights on ways to care for communities and support indigenous well-being. This ranges from specific knowledge about natural resources to care-based practices. Orally and musically transmitted, narratives and historical events are transmitted to diverse generations in communicative norms that are often not recognized by outsiders. In the eight years I worked with the Mebêngôkre-Kayapó Indigenous Peoples who steward their homeland in the south of Pará in the Brazilian Amazon, I had the good fortune to observe the sophisticated knowledge they have about caring for their communities through diverse practices, including medicinal knowledge based on Forest and Cerrado resources and healing practices across communities. These communities are working within both Mebêngôkre-Kayapó and Brazilian health systems. For example, community members to differentiate if the patient presents a "Kuben's disease (white)", being taken for treatment in the city or if he is affected by some "Mebêngôkre disease” (Kayapó indigenous). Therefore, to consider the Indigenous Peoples as primitive, is first and foremost false, but secondly ignores the complexity of this indigenous universe and the wealth of knowledge. The third mistake The third mistake is considering Indigenous Peoples and their cultures as frozen in time. According to Dr. José Ribamar Bessa Freire, this mistake is most visible when someone imposes the imaginary of Indigenous Peoples during colonization as a representation of what it means to be "the true Indian". For example, if an indigenous person no longer is naked, using technologies such as bows and arrows, many no longer consider that individual as indigenous. On the contrary, they startsto be categorized by Brazilian Society as an "ex-indigenous person." This not only misrepresents indigenous identity but also has political implications for the rights of Indigenous Peoples today. It is remarkable that these outdated visions persist, which do not accept Indigenous Peoples as citizens of Brazil and who have the free will to choose their own individual and collective expression. The prejudice that we often see, is that owning a watch, cell phone, computer, clothes or even speaking a language different from their mother tongue can be used to negate their identity. Yet, this is, as proposed by José Bessa, interculturality, or the capacity to weave together diverse realities and build new meanings that will be added to diverse cultural traditions. A practical example of interculturality can be seen in the illustrative photograph of this text (Figure 1) where the traditional ceremony (Metoro) of the Mebêngôkre people is being recorded by indigenous filmmakers. In focus is the indigenous filmmaker Motere Kayapó who films the traditional cremony. The camera in Mebêngôkrê language (Jê) is Mekaron which also means soul, ghost. However, today they have no fear of using this tool and instead are becoming more experts and producing their own documentaries. This is a clear demonstration of the ability that they have to re-signify the objects who they have interest, naming them and learning to use them, when believed this is useful for their Peoples, such as for protection and monitoring of their territory, record of their traditional practices, dances, music, stories, and other practices. Therefore, to freeze the indigenous culture is to take away the freedom of Indigenous Peoples to innovate through other cultures - a privilege only granted to non-indigenous society - without ceasing to be who they are, or having the right to transform themselves. The fourth mistake The fourth mistake is to consider that Indigenous Peoples are part of the past. Most Latin American countries have gone through a colonization process marked by massacres, exploitation and slavery, which have led to the ethnocide of thousands of Indigenous Peoples with countless cultural losses (traditions, languages, customs, for example). Although Indigenous Peoples make up this history, it is wrong to still consider Indigenous Peoples as only occupying the past. By seeking to preserve their traditions, Indigenous Peoples are celebrating their cultural wealth and histories in the current moment. For example, art produced by different Indigenous Peoples, such as body painting techniques are important immaterial cultural heritage. Body painting is traditionally present in the daily life of different indigenous groups, with varied and complex meanings, representing the cultural identity of these peoples. Today, the same designs used in body painting are now used in different arts made by them, such as bracelets, earrings, and paintings on canvas. Just a Google search with the keyword “ethnic style” reveals, while perhaps wrongly labelled, Indigenous Peoples continue to explore diverse ways of transmission of their cultural practices in varied marketplaces and visual economies. The fifth mistake The last mistake we find is the denial of our society in relation to the role colonization and programs for “miscegenation” has played in the formation of our Brazilian society. As the Brazilian anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro said, "In Brazil everyone is Indian, except those who are not". However, unfortunately, in the Global South, especially as a strategy of their political and economic elite, they rely on the tendency to only recognize the history of the winner and/or colonizer (in our case - European) denying other peoples who were also important in this construction of "Who we are". In Brazil, for example, the colonization and ethnocide of Indigenous Peoples, the participation in the transatlantic slave trade, and the role of colonizers all formulate our roots. In conclusion, we hope that readers will reflect on these five mistakes and consider how these persistent and false narratives about Indigenous Peoples still influence outcomes today. We hope that the search for the "true Indian" be stopped, giving way for a true respect to the Indigenous Peoples rights and self-determination as well as for cultural diversity to thrive. Written by Moriah Lavey Observing the 16th International Society of Ethnobiology was my first experience with

ethnography outside of an undergraduate research methods class. And what a time it was. I came face to face both with the challenges of collaborative event ethnography in general, as well as some context specific issues that arose institutionally at the ISE. Collaborative event ethnography as a methodology, is challenging. Though valuable, it is difficult to take on a field site that is temporally constrained and incredibly jam packed. The four days of the conference were the only opportunities we had to collect data and make observations. For example, on day three, I was tired, frustrated about the language barrier, and a bit distracted due to some personal concerns that arose, and I know it impacted the way I collected data. The events that I attended on day three will not happen again, so the pictures I did not take will remain undocumented, and that is unfortunate. Additionally, even with the five of us spending multiple hours a day within the conference, there is so much that occurred that was beyond our reach. Especially in the first three days, I was consistently doubting myself, feeling like I was not seeing nor doing enough, despite the entirety of my days being spent observing and participating. Thankfully at a team meeting, Laura affirmed that this sentiment is common in doing CEE’s. Not to mention it certainly is tiring to invest the majority of your waking hours physically, mentally, and emotionally invested in the goings on of the ISE. Doing the field work was demanding, but also rewarding. To be documenting the ISE was certainly enjoyable. The events that I observed, and especially the ones I could linguistically understand, were fascinating, and the conference itself was a historic event. But outside of the challenges inherent within collaborative event ethnography, the ISE itself posed its own obstacles. As a team, I believe we underestimated the extent to which the three members who did not speak Portuguese were excluded from the events at the conference. Of the twelve events that I went to, only one was explicitly in English, while three were equipped with translation services. This limitation certainly created obstacles to my ethnographic observation, understanding, and analysis of the events that I witnessed. Not to undervalue context clues like vocal tone, volume, body language, and materials like slides and videos, but to be disconnected from what was actually being discussed, and especially from the conversations that were had in event question and answer sessions, barred me from a lot of content. Not speaking the language, however, did provide us with a powerful experiential viewpoint, that of being a participant unable to access the common language of the space. It cannot be understated how this linguistic difference impacts the ability to participate and contribute to the events. All in all, being part of a collaborative event ethnography at the ISE in Belém has been a powerful learning experience, challenging me both in ways that I anticipated and in ways that caught me by surprise. Through this experience, however, I feel myself to have grown as a person and as an ethnographer. Written by Michelle David The 2018 International Society of Ethnobiology Congress has come to a close. This conference not only created a space for people from across the world to meet, but also a space for discussion, dialogue, and collaboration. After four days of lengthy yet lively sessions, a Letter from Belem+30 was created to revisit the original 1988 Declaration. The letter was read aloud and presented on two large screens for all ISE attendees at the Closing Ceremony. One of the women invited to read the letter, a Quilombola leader, announced, “when I signed this letter, it marked one of the greatest moments in my life.” The letter included clauses that renounced existing rights violations against Indigenous Peoples, Traditional Peoples, and Local Communities; empowered Indigenous Peoples, Traditional Peoples, and Local Communities to protect their lands and knowledge; defended the inherent ties between and importance of respecting biological and cultural diversity; reaffirmed free, prior, and informed consent for both private and public projects; and called upon national governments to uphold these protections.

On the first day during the Opening Ceremony, Pepeyla Miller, President of the International Society of Ethnobiology, reminded all attendees to “communicate, communicate, communicate…and listen.” Listening to the letter as it was read, I was pleased to hear some of the proposed language from the two Forum dos Povos (People’s Forum) sessions I attended. I would like to believe that the Indigenous and Local Peoples who spoke up to defend and propose their own ideas felt some mix of satisfaction, empowerment, and hope as their ideas were presented to a large auditorium of eager listeners, knowing their audience would soon be the world. Despite the creation of the Letter from Belem+30 and all the collaboration I witnessed these four days, I can’t help but come back to one message from the opening speaker at the Closing Ceremony: “Don’t forget that we have a lot to do after this event. We have a lot to work on as researchers, as people… as partners, from the communities and the social movements we work with. And it’s necessary that we learn some more to denounce, to shout it out, to feel dignified.” Tomorrow is the last day of the ISE Congress, which should bring exciting things for Congress attendees. So far, there have been many spaces for indigenous voices to be heard, which very much differs from the normal academic conference program. The Feira de Sociobioversidade (Sociobiodiversity Fair) is certainly the liveliest part of the space, which invites different NGOs, activist groups, academic societies, and even food vendors to create a market in the midst of the Hangar. It is exciting to see Indigenous Peoples and Traditional Communities inserting themselves into the daily activities and panels. We’ve seen everything from academic panels to forums, provide space for Indigenous voices, and I don’t foresee the last day of the Congress being any different.

We’ve heard from various participants that ISE is the liveliest and most fun conference they’ve been involved with, in fact, as I’m writing this, I just witnessed researchers I know dancing between the stalls at the Feira, while Michelle and myself sit in an empty stall to catch up on work. Our team is exhausted from the CEE process, yet meetings are a rewarding space as they give us the opportunity to talk about our daily experiences and make connections across events. CEE is definitely not for the faint of heart. Sleep may be futile, but our data is not! It’s day 2 at the ISE 2018 Congress and time is already flying by. It feels like just yesterday I was a mere undergraduate student learning about collaborative ethnography on campus, and here I am working on a research team in Brazil. The transition from research assistant to field research has been difficult, but I’ve learned a lot. One lesson I’ve learned after only 72 hours in Brazil is the importance of language. I have no experience with Portuguese, and I naively did not expect this to be an obstacle in the field. Even the smallest questions like, “where is auditorium A?” become a confusing slur of words and a jumble of hand motions. It’s almost impossible to be self-sufficient with this language barrier, so the collaborative nature of our team is particularly important for me. Body language and context will suffice for basic questions, but things become more complicated during events. Since the schedule is in English, I have a general sense of each event before attending, but I am unable to get a comprehensive understanding of the content. I have felt intimidated walking into these events that I won’t understand. I am exhausted from trying to pull out the few words and phrases that I recognize and construct a possible narrative based on the event theme. Despite the challenges of a language barrier, I have been able to gain something from each event. Instead of writing down every single word (which I would do in an English-speaking event) I am able to look around the room and see how people respond to each speaker. I can also devote more time to spatial awareness, taking in the environment of each event space. My contextualizing skills are getting some great exercise as well. I’ve been reminded of the uneasy feeling of dependency and confusion that many non-English speakers may feel in the US, and I feel privileged to live in a place where most people speak the language that I’m most familiar with. There are also the multiple Indigenous languages to keep in mind, but I’ll tackle one at a time.

Luckily we have 2 Portuguese speakers (Laura and Emily) to guide us through the language barrier and ensure that we are not ordering the wrong thing at restaurants. Written by Moriah Lavey The 2018 collaborative event ethnography team for the International Society of Ethnobiology Congress has assembled! The five of us (one faculty member, one graduate student, and three undergraduate students) are in Belém, Pará in Brazil, eagerly preparing for the start of the conference tomorrow morning. I have spent the last two days exploring the city on my own, adjusting to the time difference (a meager two hours, but travel is tiring!), the language barrier, and a vastly different space. I have spent much of my time alone, walking around, taking the environment in, and anticipating this next week and a half of arduous but incredibly exciting work.

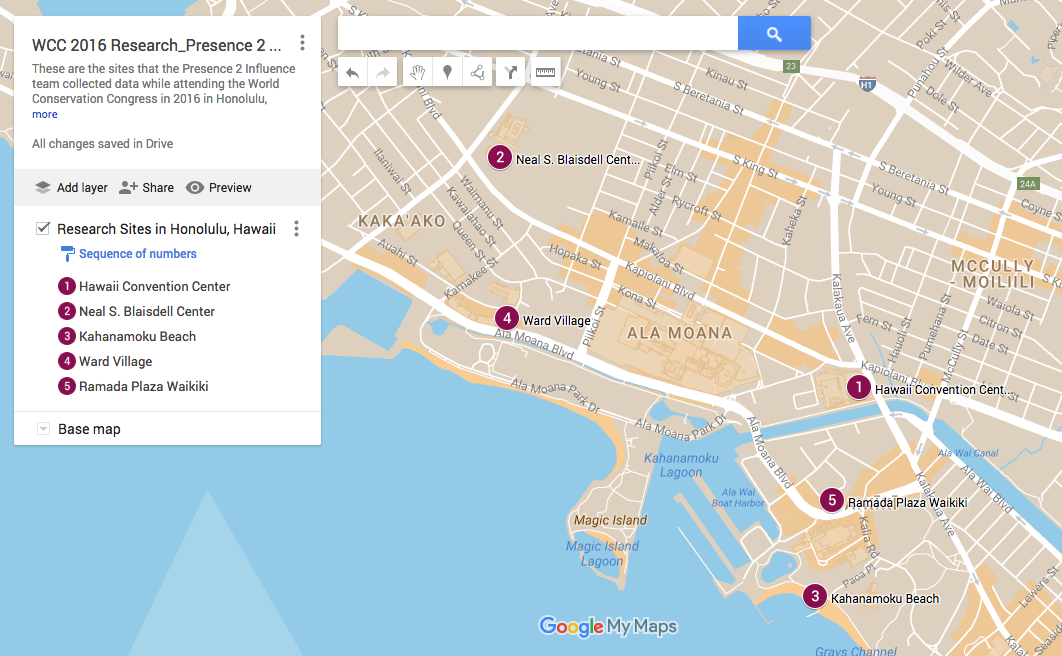

And now we are here! It really and truly is happening, with Laura adding ‘all at once’. I feel as though I spent so much time in anticipation and preparation, it is hard to make sense of the fact that the time has come. Tomorrow we will be in the field, putting into practice all that we have talked about over the last few months. We are staying at the Stada Hangar Hotel with the Hangar Centro de Conveções e Feiras da Amazônia, the site of the ISE, visible from our window. The Hangar is a massive geometric structure with windows covering the exterior that demands attention. While it certainly is daunting from the outside, the english-speaking owner of the hostel I was staying at previously assured me it feels even bigger on the inside. I am curious to see how the five of us will be able to navigate, occupy, and eventually map out the space. Our goals are lofty, but I believe in the team’s ability to do meaningful work over these next four days and beyond. I am experiencing similar levels of excitement and overwhelm, and I figure that is a good sign. Ready or not, ISE, here we come! Written by Sarah Huang This project is interested in better understanding the modes of representation, which can also be considered through consideration of how space is created. While the main site of the World Conservation Congress occurred in the Hawaii Convention Center, there were also other places around Honolulu where our team engaged with the WCC at various side events and team meetings. This map displays the location of these particular sites, which raises questions about how we can think about space in relation to a large event like the World Conservation Congress. For example, what was the presence of the WCC in Honolulu, and also how present were conceptualizations of 'Honolulu' and 'Hawaii' at the WCC? Who created these narratives about place, and how did the conference physically construct and perform those particular narratives?

For an interactive version of this map and more information about side events that we attended, please click here. |

In the field...Follow our team as we cover international environmental policy making meetings. Project Leaders:

Dr. Kimberly R. Marion Suiseeya, Department of Political Science, Northwestern University Dr. Laura Zanotti, Department of Anthropology, Purdue University Follow us on Twitter

(@Pres2Influence) Archives

December 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed